Reflections on Calderdale Conversations

Introduction

From late 2018 to the autumn of 2020 Calderdale Conversations explored new ways for Calderdale Council to engage in meaningful conversations with citizens. Our case study explores the Public Square-supported prototyping programme, which tested a series of novel approaches to citizen engagement.

The mission

Council relationships with citizens are often determined by two settings: customers who use services; and as voters, who discharge their verdict on the council once every few years. These relationships can dominate the way council and citizens engage with each other. And, as a result, engagement can become characterised by formulaic interaction that seeks to extract information from citizens, or in some cases to manage ‘customer’ relationships with citizens.

Calderdale Council wanted to establish what it initially called a ‘Big Conversation’ with residents that asked how it could overcome these settings to build new, more meaningful relationships with citizens. In doing so, the hope was this would:

- Explore the role the council would have in a future where difficult decisions are being made about the future of some services;

- Explore residents’ priorities for the future;

- Explore what the relationship (and implicit contract) between residents and the council should be.

The programme

Over visits to the Council and then two workshops, the Public Square team, working with Calderdale Council and a group of citizens who already had established links with the local authority and Calderdale’s communities, developed four working prototypes.

The prototypes that were developed were:

Four prototypes were developed and tested as part of the programme. They were:

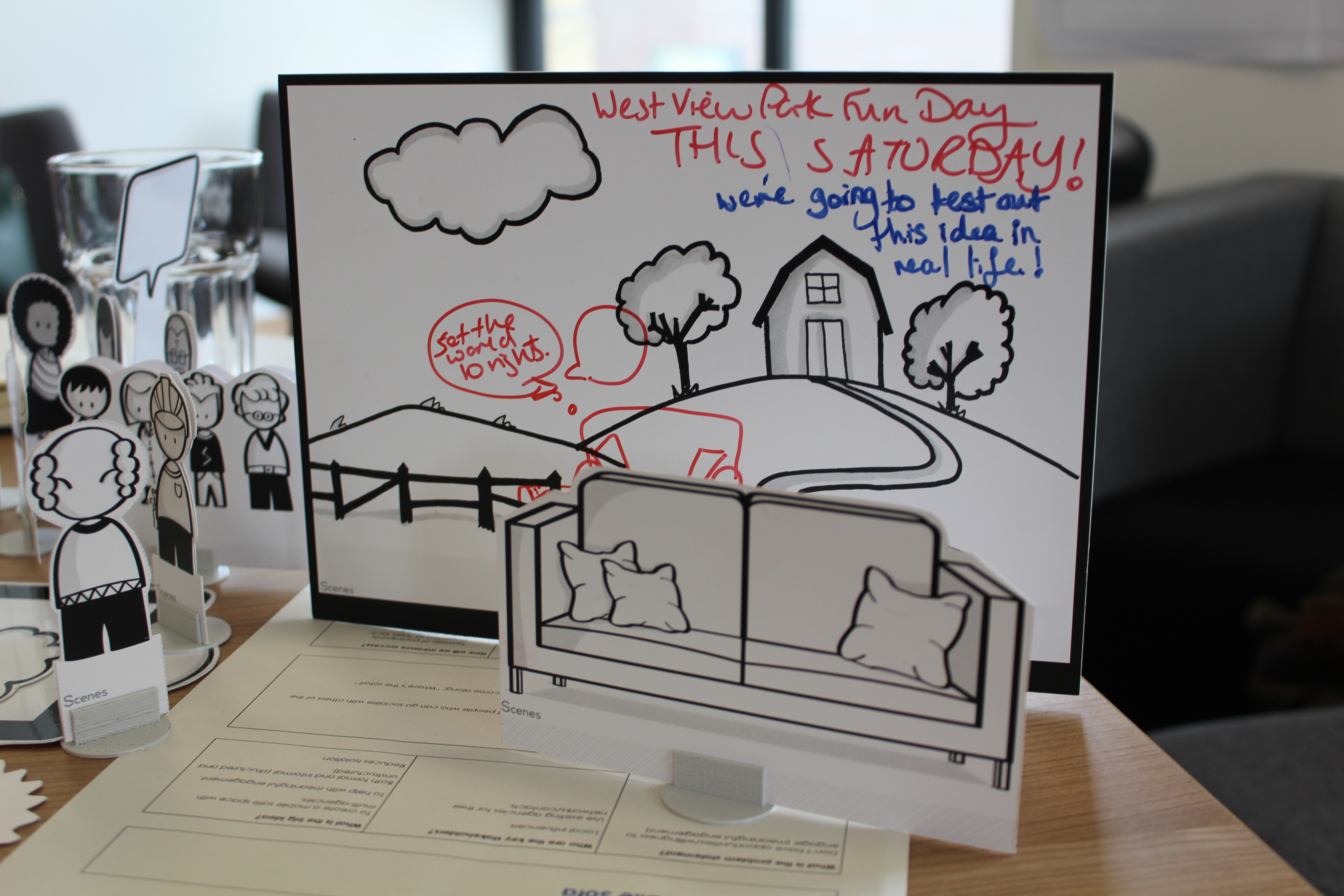

- A Listening Sofa - using a mobile sofa to create an informal space where people talk about what they wanted. This would include encouraging residents to talk with each other.

- Supermarket-style slot voting - where people could cast a publicly visible vote between particular options, similar to the slots used by supermarkets to decide which charity will receive a donation.

- Pop-up screens - either digital or analogue, these would be places to share information (including feeding back from earlier conversations) and hear from residents.

- Mobile apps - to access information about your local area, and access services. As well as a ‘two way’ aspect where you can vote on local issues, take part in discussions, and provide feedback.

The Public Square team also delivered training workshops to support staff to pick up and use these prototypes. You can read more about the prototypes, and how they were developed and tested in Public Square’s write-up of the programme’s Prototyping Report.

In the below case study, we reflect with four people involved in Calderdale Conversations, on how the project worked, what it managed to achieve, and what can be learned from it. We concentrate on one of the prototypes, in particular, the Listening Sofa, which was quickly turned into a working model and used for engagement.

Reflecting on Calderdale Conversations

Our four interviewees were: Mike Lodge, who ran the project and initiated Calderdale’s immediate interest in taking part; Cllr Scott Patient, cabinet member for climate change and resilience, who participated in the workshops; and Vicky McGhee and Janice Dawson, who as part of the Council’s neighbourhoods teams were the first people to put one of the prototypes into action. We’d like to thank them for speaking to us and sharing their reflections on the programme.

How Calderdale Conversations came together – and what it sought to achieve

Mike Lodge told us that Calderdale Conversations began as an idea with his visit to Public Square’s first event. Held in Manchester, in 2018, it brought together a disparate group of people interested in or working with or for local government.

Mike went back to his chief executive, Robin Tuddenham, to say he thought that some of the ideas he had heard at the meeting might be valuable to Calderdale, a council with a reputation for local government innovation.

What Mike brought back fired Robin’s enthusiasm: “Robin started talking about – and using some quite bold language - which is: 'democracy is broken, and we're going to fix it through this project," which was scary! I think he was talking about some of the stuff around – and I'm not making any judgments about the politics of this – but some of the divides that occurred through Brexit and some of the rise in populism and disenchantment of perhaps people who are at the poorer end of the scale of the system generally.”

That ambition was shaped further by a visit from members of the Public Square team in 2019 to the annual ‘We are Calderdale’ event run by the Council, where Robin Tuddenham first announced that the council would be working with Public Square.

At a meeting that followed the event, it became clear the council was interested in addressing elements of its social contract with residents. In common with many local authorities, Calderdale was aware that the kinds of services it provides may have to change – and that this was helping to change some elements of the relationship between residents and the authority. With a budget consultation due to be completed later that year, there was interest in using conversations from the Public Square programme to help inform that work.

This led to two workshops which developed, in total, four prototypes. All of our four interviewees attended one or both of the workshops. In the case of Mike, he led the programme - while Scott Patient was one of a small number of councillors to take part. Vicky and Janice – leaders of two neighbourhoods teams – were both invited to the workshops and were the first people to try out a prototype.

Vicky and Janice – and how they took one prototype from the workshop to the community

Vicky and Janice both are part of Calderdale Council Neighbourhoods teams. While Janice works directly for the Council serving one part of the borough, Vicky is employed by the North Halifax Partnership, serving another. They both attended the second workshop, which developed the prototype ideas in the first workshop, and made them into working, testable models. During the workshop they realised that one of the ideas being developed, the Listening Sofa, would be perfect for an event they were going to at the weekend.

Vicky said: “We'd got a big event planned that weekend. So we were quite inspired by the idea of having a physical couch in the middle of a field in this event, as well. And kind of through our community contacts felt like I reckon we could make this happen, because we knew a local charity that dealt in secondhand furniture – and we were pretty sure they'd lend us something. And we got some help knocking up a little sign as well.”

Vicky and Janice weren’t at all surprised that they were able to source a sofa and deliver it to a field quickly. They saw it as a fairly natural extension of their work in neighbourhoods. As Vicky put: “The neighbourhood staff are… a particular breed of people who are quite solution focused and just want to go and get things done. And, yeah, you're not tied up in the bureaucracy and things.”

They experimented with how they used the sofa on the day – sometimes with one sitting on the sofa, while the other hovered further away and sometimes with both moving away. That latter approach led to some interesting moments, as different people sat down and started conversations. Janice said: ”When we looked back, there was a gentleman, and a lady sat on the sofa. She was from the BAME community. And he was from the white British community. And when we went to speak to them, they both said, if the sofa wasn't there, they would never have sat down and chat together.”

Vicky said the idea behind the sofa appealed to both of them and seemed to chime with their work: “I think the public have an expectation that the council is going to solve things for them. And the council has an expectation on itself that it's there to solve problems for people. And when you're doing a Calderdale Conversation, I think you all go in as equal partners, and nobody's there to do anything for anybody else. It's a conversation and where that leads, it might be that I've got particular expertise and experience or knowledge that can link you to the right person, but I'm not going in there to do that, I'm going in just to have an equal conversation with you.”

Making an engagement programme

While Vicky and Janice were able to quickly use the sofa to great effect in an engagement setting, it was Mike’s job to make sure the programme as a whole would prove a success.

For Mike that involved ensuring adoption and understanding among staff, at what became a particularly challenging time for the Council. He said: “It's keeping change going, you know, with a group of people who are very busy, particularly since March, and with a very clear focus on a major, major problem,” he said.

Nonetheless, Mike said he did not encounter direct resistance to Calderdale Conversations: “I wouldn’t say, in the people I work with, within the organisation within the council, that there's a group opposed to this. There are people who are in it and working on it, like me and a few others, and there are people who support it in bits of their work and support the philosophy of it. And there are people who, I suppose pay lip service. And so we're not fighting against something, we're not trying to do something that people don't want to happen. “

But if not resistance, then, there was a form of intransigence. He said: “I had a conversation with a colleague that I like and work well with and have a lot of respect for. But she sort of framed the discussion as: ‘how are you [Calderdale Conversations] going to help us?’ And she's one of the good guys, you know? She's someone that is up for this. But there was a sort of ‘Oh, this will help me sort this problem out.’ And that's not really how it's going. That's not really how it's going to work.”

Culture and recognition

Mike was pleased that the programme was recognised by colleagues. And he felt that they were often receptive to its ideas, perhaps because Calderdale Council has a history of trying to change and develop its working culture in new and often challenging ways.

Indeed, Mike admitted he may himself be an example of the Council’s philosophical differences with other councils: it is rare to find a senior scrutiny officer, in the legal and democratic services department, running an engagement programme.

He said: “I've picked this up and run with it. And quite nervously at times. I've described myself to some people as having imposter syndrome. You know, this isn't my area of work. And they do exactly what I'm looking for, which is to compliment me and reassure: ‘Yeah, you're doing great.’ But my manager, and the chief executive, don’t care that I'm spending 15 or 20% of my time doing something that's not in my job description. They’re pleased I'm doing it. And I think that's, you know, it's not exclusive to me. In other areas, public health is an area I know better than some, people pick up stuff and run with it. And I think it feels like we have a good culture that allows that to happen. People aren’t saying to me, what's this got to do with you? They they're saying: ‘Tell us a bit more about Calderdale Conversations.’”

As well as the sofa, Calderdale Conversations has been working on applying other versions of the approach in different settings, including in ward work with councillors. And, if his day job was markedly different from his role working on Calderdale Conversations, it did provide him with a good vantage point to assess how the programme has been received.

“I would say, you know, a good number of people have been involved in this and have picked it up and are working with it. And I would say we talked about our priorities work in the autumn and we had discussions in every ward. And we've picked up and are using Calderdale Conversations on looking at recovery from the pandemic [as well]. So those would be the sort of tangible things I would talk about.”

Application beyond the testing

Everyone we spoke to mentioned the sofa and its impact on the programme. Mike pointed out how it was a visually striking, memorable and attracted interest from other people doing engagement work at the Council: “People [were] saying, ‘How do we get hold of the sofa?’

Similarly, both Janice and Vicky saw its value in stimulating conversation, and thought it could be useful in different settings.

Janice told us that she tried using it at a ward forum. She said: “[Regular attendees] were like, why have you got sofa Janice? And I said: Well, so we can have a conversation rather than a, you know, question and answer. So we could have a conversation before the meeting starts. That wasn’t overly successful because it was only half an hour, but it was just for that concept of having a conversation rather than a question and answer.”

Vicky said her organisation, North Halifax Partnership, is attempting to use a similar approach in some of its work following the pandemic, too.

The next stage for Calderdale Conversations is the development of a digital tool for Calderdale’s website, to be used to widen the approach for the whole council. Mike said he would like to see the idea of a more open-ended engagement and conversation used throughout the Council – and in papers to the Council has suggested that everyone who works for the council should in future see talking to citizens as part of their work. He said he will try some of the Calderdale Conversations approach in his work as in democratic services, too: “I want to see whether we can get the discussion started with the chair of the meeting saying to the councillors present: ‘Tell me what people are saying to you, in your world,’ which we would never normally do.”

Practical issues

While the programme enjoyed widespread recognition and popularity among council officers, Mike said he remained unsure about how successful the workshop and the prototype process has been for the programme. He had, he said, envisaged that the council would use Calderdale Conversations to directly change its approach to engagement, so it was embedded: “As if the council and the health service kept popping up at the local fetes and places like that.”

Working with Public Square

But the prototypes and the way of working that Public Square followed had their own process. He said: “[The prototypes should have been] an interesting 5% of the project for me. And I felt like the Public Square [team] was saying, ‘We had these workshops, this is what people told us they wanted, and therefore we're going to build them and then that’s what it’s going to deliver,’ and that didn’t quite work.”

Prototyping

In fact, Mike felt it may have been that the prototyping was applied to the wrong part of the programme. “I was thinking that [Calderdale Conversations] would be a way of liberating the organisation to go and stand in those places and talk to people without a questionnaire and without a clipboard, and find a way of bringing that back. And I think the prototype might actually have been a way of recording the discussion in a way that wasn't intrusive. And we didn’t go down that direction.”

Councillors and Calderdale Conversations

Mike also had concerns about the extent to which he and others had helped councillors become interested in and involved with the programme. “We haven't succeeded in getting widespread political support, or political ownership is probably the better word,” he said.

But that might be because the programme concentrated on a form of engagement that councillors, in their ward work, might feel they are already doing, he believed. He said, of councillors: “You know, us saying we've got to listen to people properly, it could be perceived as a challenge to what they do all the time.”

And that might, he thought reflect the fact that, while officers are able to support councillors in much of their work, that isn’t the case when it comes to ward work. He recalled hearing a councillor on a course he attended, who was asked to speak about her work as an elected member. “She was asked the question, ‘What motivated you to become a councillor? What do you do?’ And all she talked about was her ward work. She said, ‘People come to see me about this and about that.’ And I was thinking this doesn't impact on my work as an officer at all. And I think I could turn it round and say the councillors have been doing Calderdale Conversations for years, and we're just catching up.”

A councillor’s perspective

Among those councillors who did take part was Councillor Scott Patient, Calderdale’s cabinet member for climate change and resilience. For Scott, some of the attraction to the programme was in changing the nature of conversation – particularly if it would help council, councillors, and residents to talk about the deeper, underlying reasons for change.

This was, for him, about the nature of engaging: “I think it sort of helps add extra oomph really to that, and show that, you know, come election time, when you get your leaflets out – and you're promising this, that, and the other – that actually, those promises have teeth, and that people are able to engage with that process beyond the usual ‘go into a, you know, dusty hall and engage with ward forums every two or three months’. And I think that's exciting for people, especially exciting for younger people. They, I think, traditionally haven't engaged so much with politics and or local government.”

Scott told us that, with a background in environmental activism and an interest in sustainable food development, the ideas behind Calderdale Conversations were in many ways familiar to him. And he agreed that younger councillors might be more comfortable with Calderdale Conversations, generally.

He said: “Even if it's not a generational thing, it might be a 'How long have you been engaged in a particular party thing' as well, just in terms of your entrenched views. But I think from my point of view as a ‘younger councillor, or ‘newer’ councillor, as well, my sort of background [involves] active participation. So that's important to me, that's part of my values. And I think I could probably safely say that most of the younger, newer, councillors share the same ethos as well.”

For Scott, the most pressing issue – aside from recovery from Covid – is climate change. Representing a ward in the north of the Calder Valley, which has been hit by a series of floods, its effects are real and understood, as he explained. “I think what this does is give us the ability to do is to go out to those communities, more broadly, and sort of have conversations [about climate change].”

Burning platforms

Scott and Mike both talked about how much has changed since the programme had started – with our conversations taking place in late 2020. Unlike often-mentioned ‘burning platforms’ for local authority culture change – the digital revolution, an ageing population and the rise of populism – the pandemic’s effects have been swift and unavoidable for everyone. As Scott said: “We probably spent 18 months trying to develop digital development you know, and put quite a lot of money into it. And then, overnight, we're all video conferencing experts. And that's going to be meaningful going forward, no matter how we come out of this. I think that is an embedded change.”

How the pandemic has affected perspective

The shared experience of the Coronavirus, both across Calderdale and across the rest of the UK, will have lasting repercussions. And even if those changes are difficult to predict now, they are likely to be uneven and, undoubtedly, they will not all be positive. But, with the significant economic downturn we have all experienced, it certainly redoubles the need for new conversations about how places are able to renew themselves.

Calderdale, with its innovative council and thriving communities, appears to be well-placed to do that work. Scott said he believes that Calderdale Conversations is likely to remain an important part of the Council’s working philosophy.

“I'm guessing there are some entrenched cultures within local government. But from my point of view, though, it feels like, like our guys are up for this. You know, it really does actually feel like there's enough corporate interest in this and enough political interest in this, that it's got legs, it doesn't feel like it's something I'm asked about on a regular basis, how are we going to do it comes up in conversation in [the Council] Leader’s briefings, how we're going to consult, Calderdale conversations always comes up.

He said much of that will be about councillors and staff keeping the programme in the forefront of their minds. He said: “I'm trying to embed it in as much as I'm trying to ask councillors to have climate change in the front of their minds – when they're reading any, any policy documents when they scrutinise everything. You know, when I'm asked, ‘What can we do about climate change? What changes can we make? It's like, well, the obvious thing is met, keep it in the front of your mind, so that it's there as you do everything you do within the council.”