Power at Work: Transparency

How do you start to make organisations more democratic? We spoke to community network organisers and leaders in third sector to hear how they distribute decision making and power dynamics within their spaces.

This Power at Work blog series explores how small-scale change can help shift the way power is distributed in the places we work. This blog is part four - part one, (Dis)comfort & Trust is here, part two, Accountability, Honesty & Challenge is here, and part three, Unlearning & Permission by Default is here.

Hitting the Lights: Transparency & Knowledge Equity

Knowledge is power, or one type of power at least. Making knowledge more open and available through more transparent practices was mentioned across those we spoke to as something which helped create healthier power dynamics, be it for decision-making, pay structures or participatory grantmaking.

In the case of decision-making, knowing how decisions take place, where they happen, why they were made and who gets to be involved is a form of power. Transparency around organisational practices complements and reinforces other enabling conditions. Group members who have been supported to build their confidence to challenge and hold others to account can do so more effectively if they know or can easily find out what’s going on.

Internal transparency was more of a challenge for the larger, more hierarchical and formalised organisations we spoke to. Not only does it become harder for such groups to collect and share what’s happening with their members, larger organisations were also less likely to be radically experimental in their organisational and governance structures. Those we spoke to had mostly opted for traditional models of third-sector governance and the transparency reporting requirements – and routes to financial growth – that accompany them.

As we said in the first blog, power is taboo. Those wondering how to create more transparency in their group might have second thoughts about sharing with colleagues who is – and particularly who isn’t – allowed to be included in a decision making process, or who is paid what and why. Working in the open can be an uncomfortable transition, and bring its own challenges around ensuring the privacy and safeguarding of group members, particularly those whose views or identities might differ from those of the group at large.

Working in the open can be a barrier for some – a cultural shift – they might not feel comfortable going there.

From our conversations and interviews, such a transition towards greater transparency appears to work best alongside other cultural enabling conditions such as trust, comfort with discomfort and a culture of challenge.

Enabling Conditions

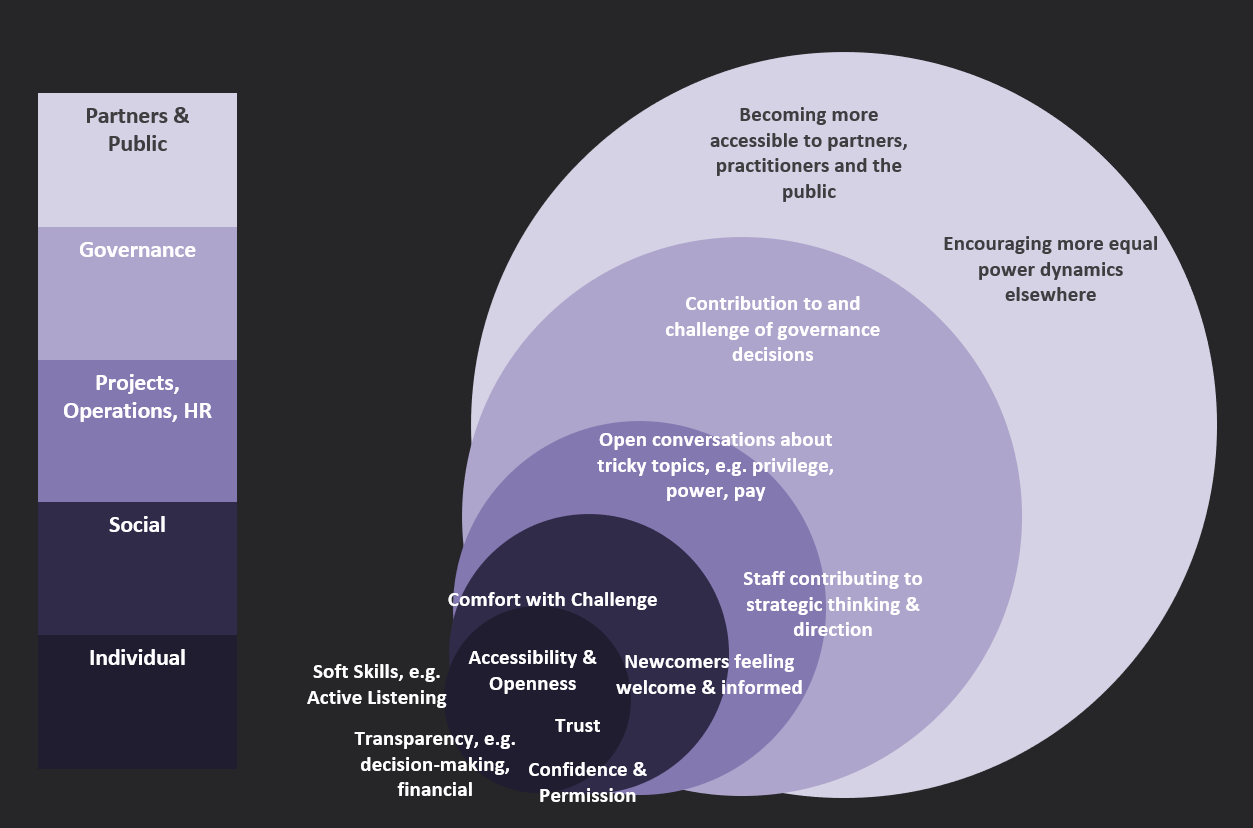

Drawing together what we heard during these interviews, we tried to map the different levels at which power shows up in organisations. In this blog series we've explored how, at an individual and social level, people are able to create more equal power dynamics in their work.

Below we visualised the set of behaviours we've explored in this blog series - comfort with discomfort and trust, honesty and challenge is here, and permissioning - as key enabling conditions. It seems these behaviours and relationships have a ripple-out effect within organisations, helping to unlock conversations on difficult and taboo topics, and enable structural change to the "hard rules" which on paper decide how we work together.

Final thoughts: A muddy path…

Reflecting on the discussions we’ve had, and the analysis above, what can we take away?

Distributing power and governance is a slow and sticky process, at any scale. It takes commitment, and it’s not as simple as changing a procedure on a piece of paper. It’s a gradual process of cultural change, of discomfort and building relationships. It’s a muddy path to try and tread, and codes of conduct and decision-making matrices may have their place in creating the ground-rules for greater participation in governance and decision-making.

It’s not easy to try and work more equitably, and nobody from those we spoke to claimed to have completely cracked the challenge. But that hasn’t stopped them trying.

Further reading

Here are a few interesting tools and inpiring thinkers who we found useful to help think about power, perhaps you'll find them interesting and useful too...

Beyond the Rules partners Dark Matter Labs' exploration of Reimagining Pay structures

The Going Horizontal movement

Jo Morfee's blogs on Bringing greater equality into decision making

Sasha Costanza-Chock's Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need

Maya Goodwill's Power Literacy field guide

Raji Hunjan and Jethro Pettit's Power – A Practical Guide for Facilitating Social Change

What we did – methodology

We spoke to twelve people working across civil society, to explore power dynamics and decision making processes. Those we spoke to were usually at the centre of a group or organisation, and had been involved in shaping what power and decision making should look like in their group.We spoke to…

- Bounded groups - organisations with a clear boundary which dictated who was in or out of the group.

- Unbounded groups - groups which are porous and enable people to freely become more or less involved in the discussions, decisions and work of the group.

- Community-oriented - groups who aim to represent the interests of a particular community of people, for example people with unique lived experience.

- Values-oriented - organisations which aren’t based around any particular groups’ wants or needs, instead organising around a shared set of values or principles.

Among this there was a great deal of variation in the size of the organisations and groups we spoke to, and the scale at which they operated. Some were hyper-local, while others were international. This brought an added level of depth and contrast to the findings, exposing difficult questions such as how to structure organisations around democratic and participatory principles at scale, and when hierarchy and exclusionary decision-making might be preferable.

This blog was written by Alex Zur-Clark. Interviews were conducted by Pandora Ellis and Alex Zur-Clark as part of Beyond the Rules, a partnership between Black Thrive Lambeth, Dark Matter Labs, Democratic Society, Lankelly Chase and York MCN exploring democracy beyond government.

Thank you to everybody who took part in the interviews and discussions which informed these blogs – Andrew Crosbie of Collective Impact Agency, Daria Cybulska of Wikimedia UK, Kelly Cunningham and Catherine Scott of York MCN, Matthew Bell of Plymouth Octopus, Melanie Nock of Co-Housing UK and many others who have chosen to remain anonymous. Thank you also to Annette Dharmi of Dark Matter Labs and Paola Pierri, Head of Design and Research at Democratic Society for reviewing and contributing to this analysis.